thanks to Breccia for publishing the story on BB Forum first.

![]() |

| Drawing byTim McDonagh, special to ProPublica |

Why Chapo Guzman was the biggest winner in the DEA's longest running drug cartel case

by David Epstein, ProPublica

For 14 months, the first thing Dave Herrod, a special agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration, did every morning was boot up his laptop and begin tracking a 43-foot yacht with Dock Holiday painted on the stern.

In the summer of 2005, the DEA had intercepted a conversation in which members of a Mexican drug cartel known as the Arellano Félix Organization discussed buying a yacht in California. Herrod and his colleagues studied the classified ads in yacht magazines and determined that the Dock Holiday was the boat the AFO members wanted. DEA agents then managed to get on board and install tracking devices before the sale went through. That’s when Herrod started watching the boat on his laptop.

Since the early 1990s, the Arellano brothers — the inspiration for the Obregón brothers in the movie Traffic— had controlled the flow of drugs through what was perhaps the single most important point for illicit commerce in the world: the border crossing from Tijuana to San Diego. Much of the AFO’s success derived from its predilection for innovative violence. The cartel employed a crew of “baseballistas” who would hang victims from rafters, like piñatas, and beat them to death with bats. Pozole, the Spanish word for a traditional Mexican stew, was the AFO’s euphemism for a method of hiding high-profile victims: Stuff them headfirst into a barrel of hot lye or acid and stir for 24 hours until only their teeth were left, then pour them down the drain.

Dismantling the AFO had been an official project of the U.S. government since 1992, and an obsession of Herrod’s since the year before that, when he’d started chasing the cartel as a rookie agent stationed near San Diego. A former athlete, he spent years guzzling Pepsi and Mountain Dew to power through long workdays. His health, like everything else, took a backseat to the AFO case.

After the sale of the Dock Holiday, the trackers showed the vessel hugging the coast of Mexico’s Baja California peninsula, rounding the tip of Cabo San Lucas, and heading north into the Gulf of California to La Paz. Once in a while, it sailed to Rancho Leonero, where Javier Arellano Félix, the head of the AFO at the time, had a beach house. Herrod knew that Javier loved deep-sea fishing, and he was convinced that the cartel’s chief executive was using the boat. So the DEA launched Operation Shadow Game. The plan: Watch the Dock Holiday to find out if Javier would be on it, then intercept the boat should it stray beyond Mexico’s territorial waters.

For six weeks, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Monsoon stood sentinel off Baja California, waiting for the yacht to venture more than 12 nautical miles off the coast and into international waters. But it never did. On August 12, 2006, Operation Shadow Game came to an end. The Monsoon set off for other duties, and Herrod left his laptop dark for the first time since the previous summer.

Two days later, he got a call at 8 a.m. from the Florida-based Joint Interagency Task Force South, which was still monitoring the tracking devices. The Dock Holiday had left Mexican sovereignty south of Cabo San Lucas. The men on the boat were chasing marlin, zigzagging in and out of international waters: out to 19 miles, back to 10 miles, then out to 15, then back to 12. The task force wanted to know whether the Coast Guard should board the Dock Holiday if the opportunity arose.

Herrod had only a hunch as to who was on the boat. The DEA had deemed the operation an expensive failure and pulled its on-the-ground surveillance weeks earlier. Agents who had worked on the AFO case for years were being reassigned entirely. Herrod figured he’d never have another chance to catch Javier outside of Mexico. Without asking his supervisors, he gave the order: Send the Monsoon back.

At 1 p.m., 13.1 nautical miles off Mexico, the Coast Guard intercepted the Dock Holiday. Herrod waited at the office in San Diego, pacing back and forth, as the Coast Guard collected identification from those on board. Agents shuffled past his cubicle asking for updates, like restless children on a road trip. After two hours, he got a message from the Monsoon: eight men and three boys on board. At 4 p.m., photographs started coming through by e-mail. The first two faces, those of the captain and a crewman, were unfamiliar. So were the next two. Could he have been wrong? Then came the fifth picture, and it took Herrod’s breath away: a mustachioed man in a pale-yellow Lacoste shirt, reclining on white-leather seats. This was “El Nalgón,” or “Big Ass”: Manuel Arturo Villarreal Heredia, the 30-year-old chief enforcer for the AFO. According to agents, he was known for his facility with knife-based torture.

Herrod had never seen the young man in the sixth photo, though he had the Arellano family’s heavy eyebrows. Next came pictures of the three children and another unfamiliar man. In the final photo, staring wide-eyed into the camera, was a compact, square-jawed man wearing a thin gold chain that disappeared under the collar of his salmon-colored T-shirt. His pursed lips were framed by stubble and his eyebrows arched in subtle confusion. Herrod and an agent sitting beside him shot out of their chairs. The man was Javier.

![]() |

| Javier Arellano Félix, the head of the AFO drug cartel, was on his yacht when it was intercepted by the Coast Guard after it strayed beyond Mexican waters. Javier was the AFO’s Michael Corleone: he left Tijuana, but was called back to the family business, and showed his talent for calculated violence. |

The youngest of the Arellano brothers, he was the AFO’s Michael Corleone. He hadn’t asked to be in the family business — had left Tijuana and gone to business school, only to be called back — but, like Corleone in The Godfather, the young overlord had displayed a talent for organized crime and calculated violence. As the head of the AFO, he had directed hundreds of killings and kidnappings in Mexico and the U.S.

Javier’s arrest would be hailed by officials in the States as a decisive victory in what may have been the longest active case in the DEA’s history — a rare triumph in the War on Drugs. “We feel like we’ve taken the head off the snake,” the agency’s chief of operations announced. I can’t believe it actually fucking worked, Herrod recalls thinking.

![]()

But did it? Herrod is 50 years old now and nearing the end of his career with the DEA. In the time he spent hunting the Arellanos, his hair and goatee went from black to salt-and-pepper to finally just plain salt. He’s proud of the audacity and perseverance it took to bring down the cartel, and he knows he helped prevent murders and kidnappings. But when he looks back, he doesn’t see the clear-cut triumph portrayed in press releases. Instead, he and other agents who worked the case say the experience left them disillusioned. And far from stopping the flow of drugs, taking out the AFO only cleared territory for Joaquín Guzmán Loera — aka “El Chapo” — and his now nearly unstoppable Sinaloa cartel. Guzmán even lent the DEA a hand.

This is the story of the investigation as the agents saw it, including accounts of alleged crimes that were never adjudicated in court. “Drug enforcement as we know it,” Herrod told me, “is not working.”

*********************************

Dave Herrod came to the DEA in 1991 from the U.S. Customs Service, looking for work with more gravity. He was 26, just two months out of the academy, when he got his first tip: Two vans, one tan and one blue, parked near a liquor store at Third and Main in Chula Vista, had recently crossed into the U.S. with one ton of cocaine. A ton of cocaine, parked in the open in Chula Vista? But sure enough, there, at Third and Main, was a tan van with the windows blacked out. Agents followed it to a house, where they found the blue van.

![]() |

| Joe Palacios |

The tip came from a man named Joe Palacios, a Mexican who would have been a DEA agent had he been born a few miles north. Instead he earned his living as a DEA adjunct, gathering intelligence in exchange for payment. Agents called him “Eye in the Sky,” because they operated him like a satellite: Direct him to a target, and he would send back information. The tip sounded preposterous.

Inside the two vans, they discovered 1.8 tons of cocaine bricks where the seats should have been. The DEA is going to be easy!, Herrod thought. He had no idea that the drugs belonged to the AFO, and that he’d just stumbled into the investigation that would haunt him for the next 20 years. But he got a hint that this was not an isolated bust when agents discovered that the vans had been let through the Tijuana crossing by a corrupt U.S. border inspector named John Salazar. After flunking a polygraph, Salazar came clean: He had been taking bribes from smugglers.

![]() |

| Jack Robinson |

A few months later, Jack Robertson — another special agent, only slightly less green than Herrod — officially opened the DEA’s case targeting the Arellano brothers. Robertson was as idealistic as investigators come: empathetic and devoutly Christian, with a knack for getting young gang members to open up. He was also ambitious, and he’d been hearing about the AFO, which had just begun to dominate the Tijuana corridor. One informant was afraid to even utter the Arellano name.

Robertson says his boss, Michele Leonhart — who would go on to become the head of the DEA — thought they could wrap the case in six months. But six months in, the case was just getting under way. The Arellano brothers kept themselves insulated from their street dealers and low-level thugs — hit men had to pass requests for permission to murder through a dispatcher, who would relay a coded answer back. So agents had to start by pressuring arrested smugglers to give up information about their superiors, and then work toward identifying the key lieutenants in Tijuana and Mexicali. These were the men who took orders directly from the brothers.

Following on the success of the vans’ seizure, the DEA began working with the Customs Service on Operation Bus Stop. The idea was to follow Sultana Express tour buses, which were thought to be smuggling drugs across the border. Palacios would tail the buses once they entered Mexico to see where they were getting loaded up with drugs. On his first attempt, he slid in behind a bus as it passed into Tijuana but was immediately pulled over at gunpoint by Mexican police demanding to know why he was following the bus. Palacios talked his way out of trouble — What bus?— but suddenly the case felt bigger.

U.S. agents were disappointed that Palacios had lost the bus so quickly. But that night, he did a complete grid search of Tijuana, scouring the city one street at a time. At 6 a.m., he called Herrod from the beach community of Playas de Tijuana, where he read the plate off a Sultana Express bus. “I just could not believe he pulled that off,” Herrod told me. He marveled at Palacios’s tirelessness, and his courage.

For months, Palacios followed buses to an AFO warehouse, where they were fitted with secret compartments and loaded with cocaine. Based on his surveillance, U.S. authorities made more than 50 arrests north of the border over the course of nine months and intercepted drugs, guns, and grenades.

The agents and their bosses were ecstatic, but Palacios was nervous. He’d noticed the AFO stepping up its countersurveillance. He spoke with Herrod about ensuring that his family would be taken care of should something happen to him. His wife had just had a baby, their fifth. Herrod tried to reassure him. “We’re doing some great things,” he said, “but if you’re getting a funny feeling, just bail. It’s not worth anybody’s life.”

Palacios was paid a few thousand dollars a month, Herrod told me, some of which he spent on gas and on hiring people to help him keep watch. Herrod urged the higher-ups on the investigation from both Customs and the DEA to rent Palacios a new car each week, so that his brown van wouldn’t be recognized. After repeated requests, Herrod said, the government finally bought Palacios a used Volkswagen Rabbit that barely ran. He didn’t end up driving it.

One Monday afternoon in March 1992, Palacios didn’t respond when Herrod paged him “911,” their code to drop everything and call immediately. Herrod called Palacios’s wife. She couldn’t reach him either. That night, Palacios’s number popped up on Herrod’s phone, but the caller quickly hung up. Desperate, Herrod and a colleague asked a Mexican police commander to search for him. “He said, ‘Oh, yeah, we’re right on it,’ ” Herrod told me.

Late that Friday, just as Herrod was arriving home for the weekend, his phone rang. It was the resident agent in charge, his boss’s boss, telling him that Palacios had been found. “Great!,” Herrod exclaimed. “Where the fuck has that guy been?”

“You don’t understand,” the agent in charge told him.

GRAPHIC IMAGES ON NEXT PAGE

An AFO enforcer had caught Palacios in his van with binoculars, a laptop, and a bedpan. He was executed, his body tossed on a hillside in Rosarito Beach, a coastal town 10 miles south of the border. Herrod went to Mexico to identify the body; it was the first corpse he’d ever seen. Palacios’s lips were swollen. His chest and arms were purple from blunt trauma. His throat had been slit from beneath one earlobe to beneath the other.

Herrod vowed to bring Palacios’s killers to justice. But they weren’t the only ones he blamed. An American agent never would have been expected to operate with so little support, he told me.

“We abused him,” Herrod said, “telling him to stay on stuff for weeks on end. Imagine doing surveillance 24/7 for 10, 12, 14 straight days. He was going to die eventually. You can’t do what he was doing, against the people he was doing it against, for that long a time and survive.”

The U.S. government gave Palacios’s family $350,000. But Herrod couldn’t stop thinking about Eye in the Sky, and the contrast between his fate and that of John Salazar, the corrupt border agent Palacios had helped catch. Salazar was sentenced to 30 years, but had to serve only five because he provided information that helped law enforcement intercept marijuana shipments. According to Office of Personnel Management records, he was allowed to keep his government pension.

That Jack Robertson’s boss thought the Arellano brothers could be caught in six months shows just how little American law enforcement knew about the drug leviathan to the south.

For the first 20 years of the War on Drugs, started by President Nixon in 1971, Mexican traffickers were a footnote, little more than border smugglers for Pablo Escobar, the Colombian billionaire drug trafficker. But in 1989, in an attempt to kill a Colombian presidential candidate, Escobar orchestrated the suitcase bombing of a commercial airliner that happened to have two Americans on board. That put Escobar in the crosshairs of the U.S. military. Four years later, he was gunned down after a massive manhunt.

As Ioan Grillo observed in his 2011 book, El Narco, “Typical of drug enforcement, solving one problem had created another bigger one.” The U.S. Navy blocked smuggling routes to Florida, and trafficking spidered along the Mexican border. Into the post-Escobar vacuum strode a cadre of ambitious Mexican criminals, including Benjamín Arellano Félix. The second-oldest of seven brothers — he was 37 when Escobar blew up the plane — Benjamín became the first head of the AFO. By the early 1990s, the cartel was smuggling in 40 percent of the cocaine consumed in the United States.

Months before Joe Palacios was killed, Benjamín threw a first-birthday party for his daughter at his ranch outside Tijuana. A home video shows the cartel family in its prime: the brothers dressed in garishly patterned short-sleeved button-downs, their wives in pendulous earrings and large sunglasses. Beneath a sprawling white tent, guests sipped from brown bottles of beer and red cans of Coke. Alongside an inflatable bouncy castle was a veritable menagerie — not just miniature horses and llamas, but also zebras, reindeer, and ostriches.

![]() |

| Benjamín Arellano Félix threw a first-birthday party for his daughter at his ranch outside Tijuana. A home video captures the cartel family in its prime, plus a veritable menagerie, including miniature horses, llamas, reindeer and even zebras |

Less obvious, but no less exotic, were the cars: the bulletproof blue Toyota 4Runner given to a top AFO enforcer, and next to it the bulletproof white Dodge Shadow that belonged to Eduardo Arellano Félix, the saturnine brother known as El Doctor because he had once been a practicing doctor. Ramón Arellano Félix’s armored Grand Marquis was something out of a video game, wired to deliver an electric shock to any stranger who touched it; in the event of a chase, a button inside would release a trail of oil.

Ramón, the fifth of the seven brothers, was building a reputation as the most ruthless killer in Mexico. Carne asada — “grilled beef” — was the term he used to describe the practice of throwing a body on a bonfire of car tires to incinerate it. Rumor had it that Ramón would sit calmly and barbecue his own dinner in the flames. He wore ruby-, sapphire-, and emerald-encrusted watches and a skeleton belt buckle with diamonds for eyes. He once shot a bouncer at a bar because the man had asked him to pour his beer from a bottle into a cup.

As brutal as the brothers were, their first line of defense was not their own men but Mexico’s law enforcement. Mexican officials’ corruption “wasn’t a matter of if, but when,” Herrod told me. The head of Mexico’s equivalent of an attorney general’s office received $500,000 a month from the cartel, a former AFO lieutenant told investigators. Certain military generals made $250,000 a month. Prosecutors were paid à la carte. The system was so effective that AFO prisoners would occasionally escape torture houses only to be returned to the cartel by the very police into whose arms they had fled.

So when Jack Robertson met Jose “Pepe” Patino Moreno, an incorruptible Mexican investigator, he quickly grew to admire the man. Robertson appreciated Patino’s humility, and respected his willingness to stand up to colleagues he knew were working for the other side. “He was one of the most decent men I ever met,” Robertson told me. “I always had a sense of trust in him that I didn’t have in anybody.” In that way, he was to Robertson what Palacios was to Herrod. In another way as well: Patino was captured by AFO members, who reportedly crushed his head in a pneumatic press and smashed his bones with baseball bats. His body, a Los Angeles Times article reported, was as broken as a bag of ice cubes.

Through the 1980s, Mexican drug traffickers had worked in relative harmony to move Escobar’s product. To impoverished Mexicans, narcos represented brave resistance to a corrupt government and imperious American law enforcement. Popular folk ballads known as narcocorridos lionized drug lords. There was enough turf and money and inventory to accommodate every criminal appetite, and the Arellano brothers and Chapo Guzmán not only tolerated each other; they worked together when it suited them.

That began to change in 1989, when Ramón murdered a man who had assaulted one of his sisters years earlier; the man happened to be one of Guzmán’s closest friends. Ramón also killed several of the man’s family members for good measure. Soon thereafter, the Arellanos declared all of Baja California their territory. “No one needed to be greedy,” Robertson told me. “But the Arellanos were like, ‘No, this is ours. Come here, and we’ll kill you.’ That did not sit well with Chapo.” Guzmán started digging the Sinaloa cartel’s first known drug-smuggling tunnel under AFO turf (a primitive one compared with the engineering marvel through which he escaped from prison last summer) and made plans to kill the brothers.

In November 1992, Ramón and Javier Arellano were at the Christine discotheque in Puerto Vallarta when 40 assassins posing as policemen burst in shooting. They’d been sent by El Chapo. One of Ramón’s bodyguards, a preternaturally poised man named David Barron Corona, shot and killed a gunman, then picked up the man’s AK-47 and held off the attackers while shoving Ramón and a top lieutenant into a bathroom. From there, he pushed them through a window and onto the roof — an arduous task, because Ramón was obese. The men clambered down a tree. On the ground, an assassin was waiting with a machine gun, but Barron killed him with his last bullet and all three escaped. Javier got away too, via a different route.

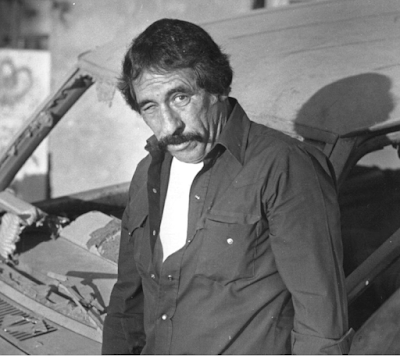

![]()

Barron hailed from a rugged neighborhood of San Diego called Logan Heights. He wore a downturned mustache and was built like a mailbox, his short arms hanging away from his body as if he’d just finished lifting weights. Skull tattoos decorated his torso, each said to represent a victim. He’d gone to prison at age 16, for killing a cross-dressing man who’d reprimanded him for urinating on a parked car.

After Barron’s performance at the discotheque, Benjamín Arellano recognized him as a fearless warrior. He bestowed upon Barron the code name “Charlie,” as in Charles Bronson, the actor famed for playing relentless vigilantes, and gave him a mission: Assemble a team of assassins who could vanquish Guzmán. Barron returned to Logan Heights to conscript about 30 enforcers from Mexican immigrant families. He offered $500 a week, plus kill bonuses. Taking out El Chapo would be rewarded with $1 million and a ranch.

![]() |

| Top AFO enforcer David Barron trained his assassins like soldiers. DEA agents found caches of weapons in an underground training facility. |

Barron hired trainers — Mexican police officers and a Middle Eastern man whom recruits knew as “The Terrorist.” He equipped his men as though they were soldiers, with bulletproof vests, hand grenades, AK‑47s, and night-vision goggles. “He never asked his employees to do anything he wouldn’t do himself,” a former AFO lieutenant who worked closely with Barron told me. He ordered his men to keep their mustaches neatly trimmed and to dress in Dockers and polo shirts. This would be a refined gang of assassins. They would kill for drugs, but never use them. The AFO built detox holding cells where any enforcer caught using would be stashed for a month. The sentence for a second offense was 60 days. A third meant death.

In May 1993, Ramón summoned Barron and a dozen of his men to accompany him to Guadalajara to kill Chapo Guzmán. They searched the city but found no sign of Guzmán, and after a week they prepared to return to Tijuana. While Ramón passed through security for his flight home, five carloads of his soldiers, including Barron, sat in an airport parking lot. Suddenly, at about 3:30 p.m., an AFO lookout spotted Guzmán, right there at the airport. He and his bodyguards were getting out of a green Buick near the main entrance.

Barron grabbed a rifle. Guzmán’s bodyguards saw him. A firefight began. The AFO hit squad fired its AK‑47s indiscriminately. Bullets flew toward the terminal and struck a woman and her nephew while they were crossing the street. Barron and two other AFO shooters poured bullets into a white Grand Marquis — they knew Guzmán owned one — killing the driver and a passenger. Guzmán himself commandeered a taxi and sped away.

When the shooting ended, several AFO members tossed their guns in garbage cans and ran for Aeromexico Flight 110 to Tijuana. It was being held because of the commotion outside. Nonetheless, a group of anxious, sweaty men were allowed to board. Ramón was already in first class, spitting on the floor — a nervous tic. When the flight took off, seven people — five bystanders and two of Guzmán’s bodyguards — lay dead or dying in the parking lot.

In the passenger seat of the white Grand Marquis, a plump man dressed in black slumped to his side, a cross dangling from his chest. He had been hit 14 times. He was Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, the second-highest-ranking official in Mexico’s Roman Catholic Church. The brothers knew right away that the cartel had made an Escobar-size mistake. “The AFO instantly went from folk heroes to villains,” a former lieutenant in the cartel told me.

![]() |

| Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo body slumped over with 14 bullet wounds |

Guzmán fled to Guatemala, where he was arrested two weeks later. He was sent to the Puente Grande maximum-security prison in Mexico, where everyone from guards to cooks ended up on his payroll. He occupied himself with chess, basketball, sappy movies, and the bands he brought in to perform — not to mention enough women that he needed regular Viagra shipments. And, of course, he continued to run his business.

The Arellano brothers managed to avoid arrest by sending $10 million and two gang members willing to give false confessions to the director of the Mexican Federal Judicial Police, according to a former cartel member. In return, the police bought the brothers time by raiding houses that the cartel had already abandoned.

Meanwhile, the AFO scattered. David Barron headed south, to Rosarito, Mexico, while his men went home to California. Benjamín Arellano also retreated deeper into Mexico. Eduardo stayed in Tijuana, but disappeared from sight. Ramón and Javier escaped to Los Angeles. They landed in tony, seaside Santa Monica, far from their hard-won turf.

The cardinal’s murder made the AFO case a U.S. priority. Jack Robertson helped create an AFO task force consisting of agents from the DEA and the FBI as well as Customs, Immigration, the IRS, the U.S. Marshals, and the Justice Department. The task force arrested some of Barron’s men as they fled Mexico and interrogated them. Slowly, it gained a keyhole view into the cartel. Then one day in 1995, a clean-cut young man with no criminal history walked through the door of the DEA office in San Diego and widened the keyhole into a porthole.

Beaten down by stress, the young man, an American whom agents dubbed “Joe Camel” for his prolific smoking, was ready to spill AFO secrets. Pickup trucks with false beds were being delivered to his father-in-law’s home in La Jolla, each loaded with a ton of cocaine. Trucks were parked in the garage, in front of the house, and around the block. He had, he confessed, been driving cocaine across America. The cartel used his father-in-law, a man in his 70s whom agents nicknamed “Grandpa,” to ferry drugs through border checkpoints, because he seemed harmless and was never searched. Grandpa explained how cartel smuggling worked and put names with faces and job descriptions. He also gave agents a piece of information that had eluded them: the identity of the Arellano brothers’ top lieutenant in Tijuana, Arturo “Kitty” Páez Martínez.

Agents were confused when they tried to check Grandpa’s criminal background, until he revealed that he had been living under an assumed identity provided by the U.S. government. Thirty-four years earlier, he had been caught participating in a heroin-smuggling ring — part of the events later fictionalized in the movie The French Connection. He then became an informant and entered witness protection, only to leave the program and return to drug trafficking. Now, for the second time, Grandpa would become a government source, allowing the DEA to mount surveillance equipment at his home. And again his crimes would pay off. He and his son-in-law were paid $100,000 for their cooperation.

The new prominence of the AFO case meant not merely increased manpower but millions of extra dollars for operations and paid informants. One AFO operative in California signed on as an informant just a day before cartel members riddled him with bullets. The man survived, and acquired the nickname “Swiss Cheese.”

After the shooting, he started collecting workers’ compensation — criminal informants who are injured in the line of duty can qualify — in addition to his informant’s pay. He also received $1.5 million from the State Department for information that helped the DEA apprehend an AFO lieutenant.

![]() |

| Duncan keeps a file labelled “Unfinished Business” that contains testimony against AFO hitmen who were never punished. |

Steve Duncan, a San Diego–based special agent in the California Department of Justice, says that after he and other agents made arrests, federal The brothers who ran the AFO: Benjamin, the cartel’s original leader; Eduardo, who had been a doctor; Ramón, known as the most ruthless killer in Mexico; and Javier, the family’s Michael Corleone (Associated Press; PGR)prosecutors would cut deals and let enforcers and traffickers go free in single-minded pursuit of the cartel’s top leaders. “The prosecutors never wanted to go sideways or down [the cartel hierarchy], just up,” Duncan told me. “So a lot of gang members who murdered people, they never got prosecuted. Some guys would give us what they wanted to give us and get off.”

None of the agents liked watching criminals walk away free — and in some cases flush with cash. But they could live with that bargain if it meant the task force would eventually work its way to the top. Bringing the Arellano brothers to justice would make it all worthwhile.

![]() |

| The brothers who ran the AFO: Benjamin, the cartel’s original leader; Eduardo, who had been a doctor; Ramón, known as the most ruthless killer in Mexico; and Javier, the family’s Michael Corleone (Associated Press; PGR) |

*******************************

After the killing of Cardinal Posadas, Ramón Arellano had to lie low. In his absence, the rank and file got sloppy. From California, Ramón sent David Barron to kill a man in Playas de Tijuana named Ronnie Svoboda, who had had the temerity to hang out with a woman Ramón was involved with. When Svoboda’s sisters, Ivonne and Luz, told the police, Ramón sent a crew to San Diego to kill them, too.

One of the hit men, who went by the name Martín Corona, watched the sisters get into their car. Ivonne was tall and lithe and exceptionally beautiful. She had spent the previous year in Paris as a model. Corona approached the driver-side window and saw her lock the door. His first bullet shattered the window. Three hit Ivonne in the head. One hit Luz, who was pregnant. As Ivonne tipped to her side, Luz’s 9-year-old daughter — who would see Corona again a month later when he and Barron arrived at her house to bludgeon her father to death — started screaming in the backseat. Corona ran, and both women survived. Sloppy.

One bungle followed another. The AFO somehow managed to procure a six-foot-long military-grade bomb for $150,000 in San Diego. In 1994, two low-level enforcers drove it to the El Camino Real Hotel, in Guadalajara, where they were supposed to use it to vaporize the building, and several of El Chapo’s associates along with it. But the bomb detonated prematurely, killing the AFO enforcers instead.

The next year, the cartel landed a commercial jet loaded with about 10 tons of cocaine on a makeshift airstrip in the desert near La Paz, Mexico. When the plane hit the sand, it sank in and got stuck. AFO workmen unloaded the coke into trucks, then tried to blow up the plane. That didn’t work, and a couple of men died. So they brought in construction equipment and tried to bury the plane in the sand instead. They managed to cover only part of it before drawing the attention of the Mexican military.

![]() |

| The AFO landed a commercial airliner with 10 tons of coke in the desert, but the plane hit the sand and got stuck. AFO operatives attempted to blow up the plane, and then to bury it. | |

All this time, Ramón was hiding out in L.A., growing his belly and his hair — now shoulder-length and dyed blond. One day in Hollywood, while hanging out in front of Mann’s Chinese Theater, wearing a Nike cap, sunglasses, and a Michael Jordan jersey, he was approached by Rupert Jee, a New York City deli owner and a regular on the Late Show With David Letterman, who was taping a man-on-the-street segment. “No entiendo,” Ramón said, as he tried to shoo Jee away. In the segment, Jee draws attention to Ramón by yelling, “Hey, everybody, it’s Michael Jordan! Look!” to the great delight of the studio audience. Slung over Ramón’s shoulder was a black satchel in which he typically concealed a gun.

In September 1997, Ramón was added to the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted” list. He fled back to Mexico, and the Arellano brothers reassembled. They were still dominant in Tijuana, but the Sinaloa cartel was gaining strength. And they could no longer operate as openly as they once had. Their unhinged violence, in fact, began to backfire.

Two months after Ramón made the most-wanted list, he sent Barron to kill a Tijuana journalist named Jesús Blancornelas, who had dedicated his life to exposing the AFO and other cartels. Among the articles that had drawn the Arellanos’ ire, his magazine, Zeta, had published an open letter to Ramón written by a woman whose two sons “served you in a time of need” and had then, she maintained, been murdered. The letter fingered AFO figures by name.

Barron’s hit squad intercepted the journalist’s car en route to his office in Tijuana and unleashed a fusillade. Blancornelas’s bodyguard was killed, and Blancornelas himself was hit four times. As Barron approached for the coup de grâce, he suddenly dropped. A fellow assassin’s bullet had flown clear of the car, struck a metal post, and ricocheted through Barron’s eye, killing him instantly. Police found him on the sidewalk, a bright-red stream oozing from his eye socket, his body collapsed on his shotgun stock, which propped him up as if he had decided to take a nap mid-killing. Blancornelas survived.![]() |

| Barron was about to finish off a journalist who’d spent his life exposing cartels when a stray bullet killed him. (Zeta) |

Months later, an informant told the FBI and the DEA the location of Eduardo Arellano’s new house in Tijuana. A corrupt Mexican police chief tipped Eduardo off and he fled with his wife, Sonia, and their two children to a safe house that wasn’t quite ready to be lived in. Sonia had to use a propane tank for cooking.

One morning, Sonia came downstairs to make breakfast. The tank had been left open all night by accident, dribbling gas into the house. As soon as she struck a match, the house exploded. The baby in her arms went flying and was critically injured. Sonia’s patrician face melted into a welter of raw flesh and blisters.

Eduardo sent Sonia and the baby north for treatment, to the burn center at the University of California at San Diego. Eduardo himself didn’t risk crossing the border. He was right to stay behind: At the burn center, Sonia met Dr. Dave Harrison, who happened to be Dave Herrod in disguise, hoping to glean information about Eduardo through small talk with his wife. By now Herrod felt like he knew the Arellanos. It was surreal, after all this time, to actually talk with one of them.

Officially, only John Hansbrough, the head of the burn center, and two other senior hospital staff members knew that Herrod was posing as Dr. Harrison. But Herrod suspects the nurses noticed that his arrival coincided with that of the special guests from Tijuana — and that he knew shockingly little about burn physiology. He occasionally followed Hansbrough into surgery but mostly stayed out of the way, and he had to offer excuses every time he was called to cover a night shift. On Christmas Eve 1998, Herrod had the bizarre experience of wheeling Eduardo’s wife out of the hospital and watching her drive away with her parents and a lawyer.

The baby, Eduardo Jr., later died, and Sonia blamed her husband for the accident. According to witnesses, she wished death upon the children of his assistant, because he hadn’t gotten a stove ready. Eduardo’s brothers were incensed by her behavior and feared she might go to the police. In October 2000, Benjamín ordered Sonia killed. Javier gave instructions for the murder. Sonia was strangled with a tourniquet and her body was dissolved into pozole. Benjamín told Javier that, should Eduardo ever ask what happened to Sonia, he was to be told that she had fled to the U.S. But Eduardo never asked.

For a group that counted family as perhaps its lone object of loyalty, the murder of one brother’s wife was an act of supreme desperation. The Arellanos couldn’t bribe their way out of everything anymore — they could only kill their way out. When Sonia’s mother and sister began asking questions, Benjamín ordered them killed too. The women were pulled from their car at a busy intersection and never seen again.

*****************************

On January 18, 2001, Mexico’s highest court handed down a decision that gave the DEA new leverage: Mexican citizens could now be extradited to the United States to face drug charges. Chapo Guzmán escaped from maximum-security prison the next day, reportedly wheeled out of the facility in a laundry cart.

![]() |

| Kitty Paez 1st Mx.Trafficker extradited to US |

Kitty Páez, the AFO’s top lieutenant in Tijuana, had been arrested several years earlier and now had the honor of becoming the first Mexican drug trafficker extradited to the U.S. He was charged with engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, which carried a mandatory life sentence for cartel leaders. Páez was the highest-ranking AFO member authorities had ever captured, one rung down from the brothers.

Herrod had by now taken over for Jack Robertson as the lead AFO case agent. He met with U.S. prosecutors when Páez was first arrested in Mexico and says they swore that if they ever got their hands on Páez, they would offer a plea deal only if he agreed to provide information about the brothers. Once extradition occurred, however, Herrod says all that tough talk melted away. He claims that, faced with a potentially long and difficult prosecution, senior officials in the U.S. Attorney’s Office began discussing a 30-year plea deal with no requirement to cooperate.

As far as Herrod was concerned, any deal that didn’t compel Páez to talk about the Arellano brothers would be a betrayal of the strategy that had driven the case. After all the small fry — the drivers and smugglers and enforcers — the task force had at last gotten someone who could confirm the brothers’ orders to kill and kidnap. Why wouldn’t prosecutors do everything they could to get information out of him?

Herrod told me that high-level officials from the DEA and the Justice Department met several times to discuss requiring Páez to cooperate or else face trial. He asked Laura Duffy, a federal prosecutor who spent a decade on the AFO case, to hold off on making a final decision until investigators and prosecutors could discuss the matter as a group one more time — but to no avail. Word came down that very same day: The U.S. Attorney’s Office had reached a plea agreement with Páez. He would serve 30 years and would not have to provide any information or even acknowledge his affiliation with the Arellanos. (Duffy told me that she was under no pressure to resolve the case quickly, and that she’d believed Páez would cooperate eventually.) Disgusted, Herrod and his fellow agents realized they would have to go after the brothers some other way.

In the summer of 2001, Herrod discovered that Ramón’s wife, Evangelina, was renting a house somewhere in the expensive Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. There was a brazenness about it that taunted him. Herrod felt a surge in his chest when he pulled up to a house that had a red Dodge Durango with Tijuana tags sitting outside. His team got a Durango skeleton key from Dodge, stole the car for a few hours while Evangelina was out, installed tracking devices, and then returned it to the same spot.

That fall, the agents learned that Ramón and Evangelina’s 12-year-old daughter, Paulina, was attending an elite private school known for educating the children of Hollywood celebrities. In a stroke of luck, a DEA employee happened to have a friend who worked at the school. Agents encouraged the friend to make small talk with Paulina, and learned that she would be ringing in 2002 at Lake Tahoe. The Arellanos always got together for holidays, and Herrod had heard that Ramón liked Tahoe. Of course he would travel from Tijuana to celebrate with his family.

The DEA rented cabins at Lake Tahoe, one just 50 feet from where the family would be staying, and sent tech specialists to set up cameras inside and outside the Arellanos’ rental. They finished and rushed out of the house moments before Evangelina arrived, sans Ramón. It was a few days before New Year’s, and a cadre of agents was on 24-hour surveillance. When Evangelina and Paulina went skiing, agents traced sinuous arcs down the mountain behind them.

By New Year’s Eve, there was still no sign of Ramón. But when the family emerged from the house that evening, Paulina was carrying a pillow and suitcase. She’s going to spend the night with her father, the agents thought. The family piled into the Durango — the one agents had equipped with trackers — and drove through the snow, a caravan of federal agents in their wake. On the hunch that the Arellanos would join the thousands of reve lers at Caesars Tahoe, as they had in years past, agents were sent ahead to coordinate with security at the casino so that cameras could be used to track the family. Herrod recalls the adrenaline of the hunt. “It’s beyond belief how pumped we were. To follow a family in a crowd of 100,000 people is frickin’ nuts,” he told me. “It was the very best surveillance we’ve ever done.”

The family walked to an empty restaurant in the back of the casino, away from the celebration, and sat. Not eating, barely talking, just waiting. The agents waited too, for one of the world’s most wanted men to come and scoop up his daughter with her pillow and suitcase. A raid team stood by with keys that could open any room in the hotel.

The family sat. And sat. The ball dropped in Times Square. Then midnight in Tahoe came and went. Agents who had been sitting bolt upright slumped in their seats. Around 1 a.m., Paulina, her grandparents, and her nanny got up and headed back to the cabin. Evangelina walked into the casino and picked up a phone. Agents watched on security cameras as she gesticulated in argument with someone on the other end. Ramón never showed.

The task force, however, was about to catch a massive break. On the morning of February 10, 2002, police in the vacation town of Mazatlán, Mexico, pulled over a white Volkswagen Beetle. Ramón was patrolling with two of his men, hoping to catch one of the Sinaloa cartel’s kingpins out in the open during Carnival. Ramón was carrying a high-ranking Mexican federal-law-enforcement credential that should have allowed him to talk his way out of any trouble with the police. But something went wrong.

A DEA informant later claimed that Ramón had been given false intelligence by a Sinaloa operative and lured to Mazatlán, where police friendly to Guzmán were waiting. But according to another informant, Ramón’s bodyguard simply misunderstood Ramón’s command to stay cool when they were pulled over. He got out of the car and started firing, and the traffic stop turned into a shoot-out. Ramón and a police officer ended up an arm’s length apart, guns drawn, shouting their law-enforcement credentials at each other.

![]() |

| Ramon is on the right |

w

itnesses reported that the officer yelled for Ramón to get on his knees, and that Ramón began to comply. The precise details of what followed are unclear. But it seems that in an attempt to take the officer by surprise, Ramón fired while bending down. The officer returned fire. One point-blank bullet to the heart from Ramón’s gun killed the officer, and one point-blank bullet to the head from the officer’s gun killed Ramón.

The picture in the local paper the next day showed two bodies on the ground, close enough to touch each other. Ramón had shaved his head, and because he’d had his stomach stapled he looked at least 50 pounds lighter than when he’d appeared on Letterman. It took a week for the DEA and the FBI to confirm that the dead man was indeed Ramón.

Ramón had often promised to kill the entire families of anyone who cooperated with the authorities. But now he was gone. Kitty Páez’s lawyer contacted the U.S. Attorney’s Office. With Ramón out of the picture, Páez wanted to discuss cooperating in return for a reduction of his 30-year sentence. Soon, Herrod was spending eight to 10 hours a day talking with him. Páez was a veritable AFO search engine, ready with an answer to any question, from names of lieutenants to smuggling tricks to the structure of the cartel hierarchy.

Mexican authorities were emboldened as well. A month after Ramón’s death, the Mexican military arrested Benjamín Arellano, the 49-year-old cartel mastermind, in a house in Puebla, southeast of Mexico City. Javier — at 32, the youngest of the brothers — was left to lead the cartel.

As the AFO teetered, a new informant emerged: Chapo Guzmán’s attorney and confidante Humberto Loya Castro. He met with agents in restaurants and hotels in Mexico City and Tijuana. He wore elegant suits, carried Montblanc pens worth thousands, and wielded a politesse incongruous with the world of drug smuggling. Even more unusual, he came with the blessing of his boss. “I met with my compadre,” he might say, meaning Guzmán. “He sends his regards.” Herrod told me there were obvious downsides to working with Loya. But El Chapo’s attorney offered precious information. His tips, for example, led to the capture of the AFO’s “chef,” the man who had developed the recipe for pozole. He also saved the lives of several Mexican officials by alerting the DEA that they were going to be murdered.

Loya was a fugitive, so agents needed special permission to speak with him. He claimed he was cooperating in the hope of having U.S. charges dismissed — he had been indicted in San Diego, along with Guzmán, back in 1995, for drug trafficking. But he continued to cooperate after the charges were dropped. By passing tips to DEA agents, he was able to undermine the AFO and therefore help his boss. As an agent who declined to be identified put it: “We dismantled a rival cartel because of information that [Guzmán, through Loya] was able to provide. It definitely helped Sinaloa stay in power.” At one point, agents heard through intermediaries that Guzmán himself was interested in becoming an informant, but top DEA officials wouldn’t grant the same special permission that had been extended for his attorney.

Meanwhile, the DEA had set up a hotline and put up posters at border crossings promising up to $5 million per brother for information that led to their arrests. Most of the tips were nonsense. But late on Christmas Eve in 2003, a call came from a man claiming to be part of the security detail for the AFO. Agents dubbed him “Boom Boom.” He wanted out of the cartel, and was willing to give up AFO radio frequencies. The DEA started listening, nearly around the clock. For the first time, they could overhear a drug cartel operating in real time. It took a while to get used to the coded language. A reference to an “X-35 with shorts, pantalones, and frijoles” meant an armored car with handguns, rifles, and bullets. The office of Zeta, the investigative magazine, was “X-24.” Cocaine was “varnish.” Mexican federal police officers were “Yolandas.” Over two years, the DEA recorded the AFO planning 1,500 kidnappings and killings, including those of at least a dozen Mexican police and government officials. Agents had to listen — in real time — to people being tortured; they were often helpless to do anything about it. “Cover his mouth,” one man said in Spanish, chortling, after a long scream. “Cover his mouth! Cover his mouth!”

Among the half million AFO radio transmissions that the DEA recorded was one that led them to intercept a phone conversation about the purchase of a 43-foot yacht. This was the information that gave rise to Operation Shadow Game and the 2006 capture of Javier Arellano on the high seas, as the Dock Holiday chased marlin into international waters. Once in port in San Diego, Javier was loaded into a bulletproof Suburban and driven five minutes through closed streets, under the gaze of government snipers, to a federal detention center. His arrest was the cartel’s death knell. Soon after, AFO lieutenants began defecting to rival cartels or splitting into their own factions.

In 2008, one of Eduardo’s confidantes gave him up — he was the last brother who was alive and free and had any experience leading the cartel. He was captured in his home in Tijuana. The eldest brother, Francisco, who’d helped get the cartel started but had been in prison during most of his brothers’ reign, was the last to meet his fate. He was at his 64th-birthday party in Cabo San Lucas in 2013 when a man dressed as a clown walked in, shot him dead, and walked out.

Two decades after Jack Robertson opened the case against them, every one of the Arellano brothers who had helped run the cartel was either dead or behind bars. Benjamín and Eduardo were extradited to the United States. It was a crowning achievement for the DEA, complete with promotions, political appointments, and chest-puffing press releases.